1. Presentation

Managing car demand is fundamental to control urban sprawl and trip distances. Parking policies have been gradually changing, especially in urban centres, by implementing more restrictive measures that seek to balance the different (often competing) needs of urban land-use.

In addition to pricing strategies (See Parking Pricing for vehicles), managing the supply of car parking is fundamental to car demand management. When implementing a cycling plan, parking management can be divided into two approaches, the relocation of space towards bicycles and increasing bicycle competitiveness. The first approach is more suited for areas were space is highly contended, while the second is better suited to complement traffic calming measures or to change parking’s public image.

2. Objectives

- Reducing car demand in urban centres.

- Creating more ecologic, livable and safe streets for pedestrian and cyclists.

3. Measure’s importance

Restricting parking discourages automobile circulation, reducing pollution and congestion and freeing space for non-motorized travel modes.

1. Good Practices

– Parking management usually starts with parking pricing (See Parking pricing for vehicles). Restricting parking availability is usually reserved for situations where the available pricing options have been exhausted, where space is highly contended and is necessary to find space for other means of transportation (parking is always the first to go), or situations where conditions are very favourable to more sustainable transports and there’s a clear intent to privilege them (for example near public transportation interfaces, or in main centres).

– When managing parking one can opt for the suppression of parking spaces or relocating them to less driver friendly spaces. In both cases, this decision usually results in the need of occupying the freed space with parking for other functions.

– This measure may be applied in public and private parking. It’s important to remember the role Municipal Director Plans (Planos Diretores Municipais – PDM) have in defining a city’s parking offer and that they can also be used to restrict it, once the tradition of only defining parking minimums is past.

– Evaluate the actions to be implemented according to their impact on objectives of the land use and transportation sustainability strategies. It’s necessary to consider that relocating parking spaces may have negative consequences on these new areas.

– This measure is usually accompanied by strong popular protests. To overcome this, it’s necessary to assure that automobile parking was removed to supply the citizens with an asset, which, in the case of a cycling strategy, commonly corresponds to creating cycle paths in the place of parking spaces. Yet in beginner cities, where the demand for cycling is residual, this justification may not be enough to convince the citizens. Before advancing with the suppression of parking, is necessary to involve the local population in alternative relocation solutions.

– Offer convenient and updated information on the availability, price and location of car parking.

– This information should be complemented with data on non-polluting options, i.e. indicating the location of nearby public transportation and bicycle stations and offering a price comparison (If drivers are informed of the advantages of cycling and public transportation over the car, they will be less resistant towards car restriction measures – See Information).

2. Actions

| Replacing car parking for bicycle parking Relocation or removal of a small number of street car parking to install bicycle parking. |

| Replacing car parking for cycle paths Relocation or removal of lateral street car parking to implement a cycle path. Car parking spaces can be relocated to the extremes of those cycle paths, implementing park & Ride systems. These associate car parking to bicycle or bicycle parking provision. This option allows for sustainable options to be placed on the entrance of the city centre. |

| Reducing car parking availability Relocation or removal of public parking in areas where there is an intent to reduce car use demand as a complementary measure to a traffic calming strategy. Cars are relocated to the periphery of urban centres. To promote exchanges between cars and more sustainable alternatives, namely bicycles and public transports, Park & Ride and Park and Bike options can be implemented in the periphery. (See Horizontal and vertical road deflections, Road narrowing, Car connectivity restrictions, Limited car access areas, Road user charging, Limited speed zones). |

| Regulating car parking limitso Reduce, loosen or abolish maximum parking limits in the Municipal Director Plans. Example: The Boston Metropolitan Area Planning Council (MAPC) conducted a study on available parking in residential areas. It concluded that, in average, each household only needs 0,73 spaces, but the excessive supply leaves 30% of the available spaces empty during peak-time. The report offers several management and design solutions to counter this trend. Learn more: https://perfectfitparking.mapc.org/assets/documents/Final%20Perfect%20Fit%20Report.pdf |

| Limiting car parking Introduction of maximum parking limits in the Municipal Director Plan (for both public and private parking) in areas where sustainable transports are available (main centres, close to public transportation or close to schools with a strong cycling infrastructure surrounding it). |

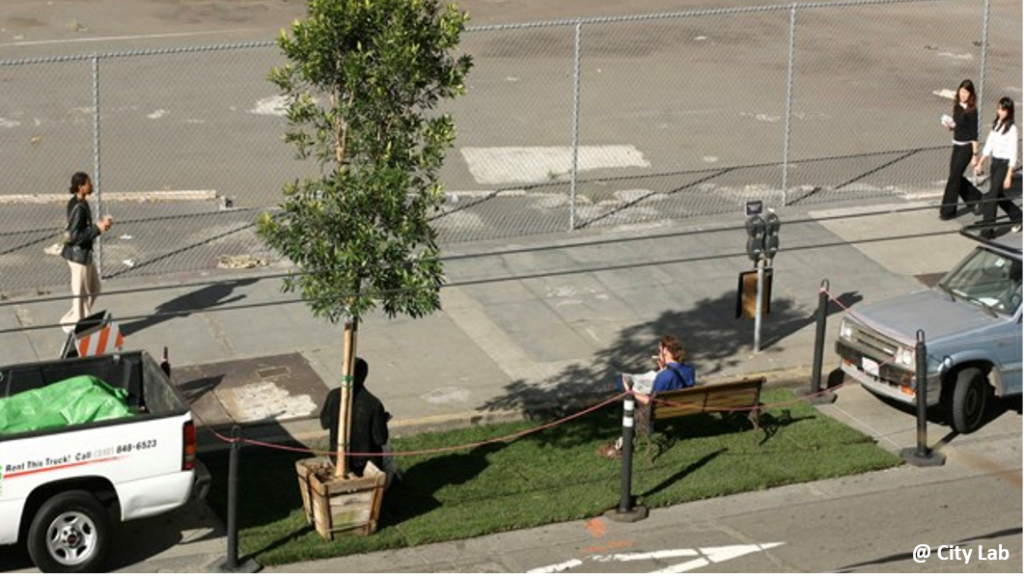

“PARK(ing)” Day is a worldwide event where street parking spaces are occupied by temporary parks. Authorities encourage residents and local businesses to create proposals for mini-parks. The creators have total liberty with the design, being only restricted by a small set of rules aimed at maintaining safety. If the proposal is accepted, the residents are responsible for constructing, maintaining and, in the end, cleaning the chosen area.

Learn more: www.citylab.com/life/2017/09/from-parking-to-parklet/539952/

1. Impacts

| Mobility system efficiency By discouraging car use, traffic congestions affecting public transports are reduced. |

| Livable streets By limiting parking and discouraging car use, the number of vehicles in public space is reduced, creating more safe and safety for pedestrians. However, if the measures aren’t properly applied, surrounding areas may suffer adverse effects. |

| Protection of the environment Reducing the number of private vehicles in circulation reduces pollution levels. Yet, surrounding areas may be affected by congestion and its negative effects if the measures aren’t properly applied. |

| Inclusion, equity and accessibility It might contribute to the mitigation of equity problems, i.e. problems associated to air quality and road accidents. In addition, by promoting low cost transports over car use, namely bicycle and public transports, equity between economic classes is facilitated. |

| Safety and comfort Parked cars are associated with the risk of collision with pedestrians and cyclists. Reducing the number of cars, especially those looking for parking spaces, might increase security. |

| Economic value There is few evidence that parking fees are prejudicial to corporate investment or local trading. The fees implemented create income that can cover the initial investment and/or finance other mobility measures. |

| Awareness and acceptability No impact. |

Legend:

| Very positive | Positive | Neutral | Negative | Very negative |

2. Barriers

| Legal There might be obstacle for public entities when regulating private parking. |

| Finance No barriers. The costs are covered by the income attained. |

| Governance There might be difficulties when coordinating public and private interests, especially those of companies and stores that offer parking. |

| Political acceptability There might be some resistance in creating barriers to car circulation and/or allowing the construction of uses that will increase the scarcity of parking and other services. However, these barriers might be overcome with poignant and comprehensive campaigns. |

| Public acceptability There might be some resistance in creating barriers to car circulation and/or allowing the construction of uses that will increase the scarcity of parking and other services. However, these barriers might be overcome with poignant and comprehensive campaigns. |

| Technical feasibility Demands a multidisciplinary study of the intervention area. Normally, the government authorities involved have teams with the necessary knowledge or the means of contacting them. |

Legend:

| No barrier | Minimum barrier | Moderate barrier | Significant barrier |

3. Budget

Requires the acquisition of services create a comprehensive parking plan.

Costs vary according to number of implemented actions.

It might be necessary to account for labour resources and materials to modify existing parking spaces.

Modifications may include the construction of pedestrian walkways, cycle paths and/or bicycle parking.

Case study 1: Paris (France)

In Paris, since the mead 1990’s that legal, physical and financial constraints on private cars have been implemented. Many of the parking spaces were replaced by cycle paths, tram tracks, public and private bike sharing parking, motorcycle parking, and parking for people with disabilities.

Impact:

| Mobility system efficiency Discouraging the car leads to traffic decongestion and the increase in transportation efficiency. In addition, the transport system was supplemented by the added tram tracks. |

| Livable streets Many of the cycle paths are being designed to create greater ties between the population and the urban landscape, namely the river front, during their day-to-day courses. |

| Protection of the environment There has been a 30% air pollution reduction between 2001 and 2017. |

| Inclusion, equity and accessibility No data. |

| Safety and comfort Paris cyclists claim to feel unsafe due to the drivers hostility. |

| Economic value No data. |

| Awareness and acceptability No data. |

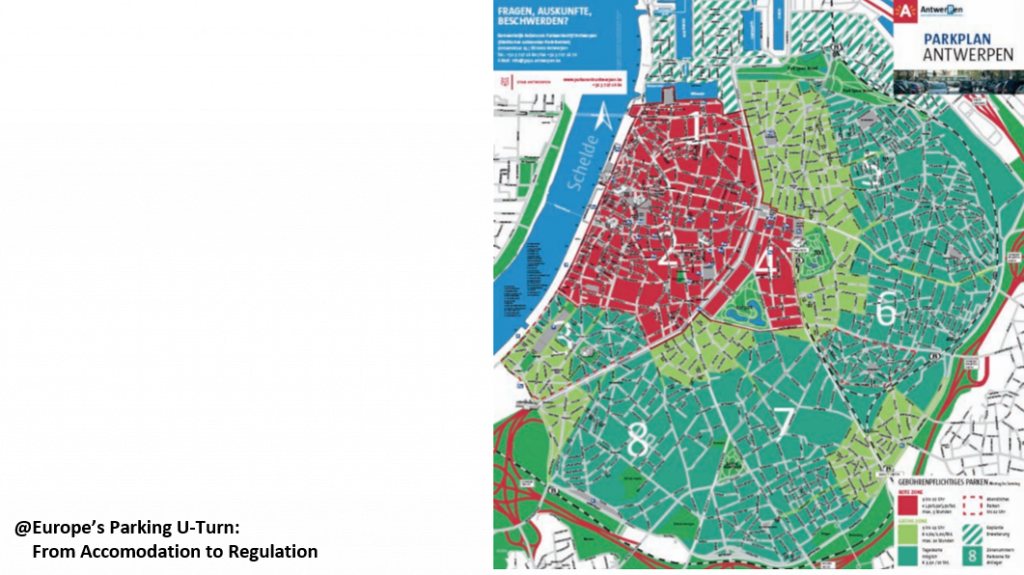

Case study 2: Antwerp (Belgium)

- Since 2001, the semi-private company GAPA has:

- Installed parking meters;

- Strengthened parking meter enforcement through the auxiliary police and their own enforcement team;

- Diversified parking meter paying methods (coins, telephone messages, telephone calls and individual car rechargeable card readers);

- Emitted digital parking licenses for interested residents (2 licences per household);

- Imposed minimum private parking limits by closing or converting unregulated garages;

- Provided financial incentives and legal and informative services to facilitate private parking sharing;

- Reserved parking for car poolers;

- Invested the generated income in mobility projects and a bike sharing programme.

Impact:

| Mobility system efficiency Due in great part to the application of parking restrictions, there was a 3% increase in public transportation use between 2000 and 2006. |

| Livable streets Due in great part to the application of parking restrictions, there was a 66% and 61% increase in pedestrian and cycling trips, respectively. By improving pedestrian conditions, the streets became more livable. |

| Protection of the environment Between 2000 and 2006, there was a 50 reduction in car use, resulting in less pollution. |

| Inclusion, equity and accessibility No data. |

| Safety and comfort The increase in pedestrians and cyclists has created more vigilance, while the reduction in vehicles has created more safety and comfort. |

| Economic value The generated income allowed the financing of mobility projects and a bike sharing programme. |

| Awareness and acceptability No data. |

Legend:

| Very positive | Positive | Neutral | Negative | Very negative |

Allemandou, S. (2017) Can Paris become the world’s bicycle capital? France 24. Accessed 8 July 2019. Available at: https://www.france24.com/en/20170905-france-paris-cycling-bikes-transport-pollution-hidalgo-copenhagen

Kodransky, B. M., & Hermann, G. (2011). Europe’s Parking U-Turn: From Accommodation to Regulation. Accessed 3 July 2019. Available at: https://itdpdotorg.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Europes_Parking_U-Turn_ITDP.pdf

Paris (2017) Vélo et transports écologiques au centre de Paris. Accessed 8 July 2017. Available at: https://www.paris.fr/actualites/velo-et-transports-ecologiques-au-centre-de-paris-4407

Paris en Selle (2017) Barométre des villes cyclables. Accessed 8 July 2019. Available at: https://parisenselle.fr/barometre-des-villes-cyclables/

Schneider, B. (2017) How Park(ing) Day Went Global. City Lab. Accessed 26 July 2019. vailable at: https://www.citylab.com/life/2017/09/from-parking-to-parklet/539952/

VTPI. Victoria Transport Policy Institute (2018). Parking Management. Online Transportation Demand Management (TDM) Encyclopedia. Accessed 19 June 2019. Available at: https://www.vtpi.org/tdm/tdm28.htm#_Toc128220496