1. Presentation

Provision of different types of financial incentives to encourage the use of sustainable commute modes, particularly cycling (such as monetary incentives, material incentives, reimbursement of bicycle purchases, etc.).

2. Objectives

- Creating economic incentives and other benefits for cycling;

- Rewarding sustainable travel and cycling over individual motorized transport;

- Promoting greater fairness in access to bicycles, contributing to a more democratic public space;

- Actively promoting the mobility paradigm shift.

3. Measure’s Importance

This type of measure motivates and rewards the shift towards sustainable mobility behaviours and cycling in particular, ensuring individual means for cycling and promoting greater social acceptance, which is particularly relevant in the context of starter cycling cities.

1. Good Practices

– Incentives should be integrated with other efforts, such as cycling infrastructure and education.

– Benefits can be proportional with how often individuals or organizations use sustainable modes.

– Monitor citizens’ adaptation to change and reformulate measures to meet user needs without compromising sustainable ideals (See Management, Monitoring and Maintenance).

– Explain the principles behind the measures to make it clear its importance and impacts (See Information).

2. Actions

| Incentives for the acquisition of bicycles and cycling equipment Provide incentives (such as tax deductions, interest-free loans) and discounts for the purchase of bicycles, pedelecs, electric bikes, and cycling equipment. In some cases, companies/ organizations give bikes to the employees (as an alternative to the company car). Learn more: www.bike2work-project.eu/en/Public-Policies/Buying-Schemes/Overview/; radkompetenz.at/en/2336/company-bicycle-instead-of-company-car/. |

| Cycling Subsidies Monetary incentives can motivate and reward mobility‐shift behaviours and may include: small payments, mileage allowance payments (providing mileage reimbursement), parking cost reimbursement (offering the equivalent value of subsidized parking to those using sustainable travel modes). Note: Monetary incentives raise problems if they have tax implications. |

| Non-monetary Incentives In-kind incentives (such as the provision of bicycles and related equipment) or in non-taxable forms, including additional paid vacations, more free time, or discounts on local commerce. |

| Benefits for public and private entities In many countries, tax systems support the use of sustainable modes, promoting cycle- friendly environments and thereby improving sustainability and the citizen’s health. These supports include subsidies or tax breaks for companies and public bodies that provide bicycles to their employees and create the necessary adaptations to make the workplaces attractive for cycling. Learn more:www.bike2work-project.eu/en/Public-Policies/Fiscal-incentives/Overview/ |

The Biklio app (available in several European cities, including some Portuguese) works a network of local businesses where customers that arrive by bike are entitled to a set of offers or discounts. Thus, with a reduced cost supported by businesses, the app rewards cycling and attracts new customers.

Learn more: https://www.biklio.com

1. Impacts

| Mobility system efficiency Financial incentives promote an increase in the modal split of the bicycle, thus contributing to less traffic and greater efficiency of the mobility system. As the number of bicycle users increases, the city will need to invest in more cycling infrastructure (which is cheaper to build and maintain than road infrastructure). |

| Livable streets Increasing the bicycle use in daily commutes make friendliest cities, human scale cities, and promotes more livable streets. |

| Protection of the environment Less car travel on daily commutes reduces pollution and improves the environment. |

| Inclusion, equity and accessibility By raising the status of bicycles and removing the stigma of cycling, particularly in the workplace, these measures increase transport options for everyone, including individuals from disadvantaged backgrounds or those unable to buy cars, promoting greater social equity. |

| Safety and comfort Increasing the number of bicycle users in daily commuting contributes to increasing safety and comfort for all, but bicycle safety measures should also be implemented. |

| Economic value Evidences show that increasing the number of bicycle users in daily commuting has helped to boost local commerce and economy. |

| Awareness and acceptability Financial incentive measures represent an important effort to effectively raise awareness and overcome barriers to cycling. |

Legend:

| Very positive | Positive | Neutral | Negative | Very negative |

2. Barriers

| Legal Financial incentive measures should be developed within the country's fiscal framework. In addition, they require the establishment of rules to enable financial benefits and may require participants to sign an agreement that specifies their responsibilities. |

| Finance Financial incentive programmes have financial costs and administrative expenses, but also savings in road infrastructure and parking expenses. Local or national authorities may encourage or require the implementation of (mandatory) financial incentives by large companies. |

| Governance Financial incentive programmes may involve national and local governments, employers, workers, unions, urban and traffic and transport planners, and environmental agencies. |

| Political acceptability There may be resistance from workers and unions to some types of incentives. Local governments may not be willing to reduce parking revenues. |

| Public acceptability Support of pro-bicycle movements, but also opposition from car industry lobbies. |

| Technical feasibility Financial incentive programmes have no technical barriers. |

Legend:

| No barrier | Minimum barrier | Moderate barrier | Significant barrier |

3. Budget

| Area | Measure | Unit | Cost | Implementation year |

| Manchester Metropolitan Area (U.K.) | Business grants for CCTV security, lockers, drying rooms and bicycle hangers | 84 companies and 1228 bike parking spaces | £ 0.75 million (average £ 6,000 /grant, limited to £ 10,000 * | Information gathered from a 2017 study |

| Birmingham Metropolitan Area (U.K.) | Business grants to fund bicycle shelters, bicycle hangers, showers, hairdryers, lockers, drying rooms, CCTV security, bike repair stands, bicycles and safety equipment for business trips, toolkits and pump stations. | 27 workplaces | £ 0.20 million (average of £ 7,000 /grant, limited to £ 10,000) * | Information gathered from a 2017 study |

* Employees were required to provide part of the funding. In Birmingham’s case money could be replaced by work hours.

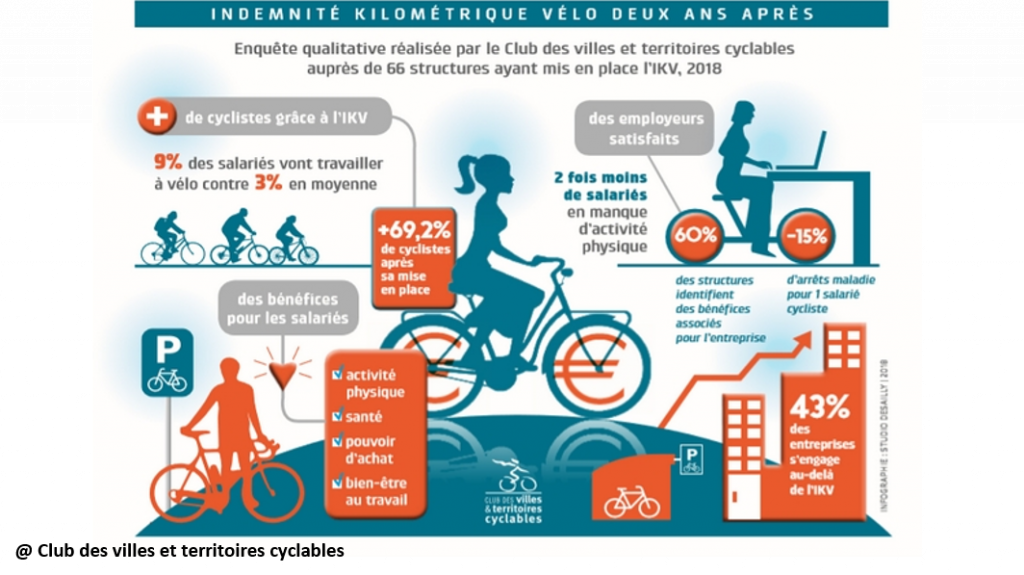

Case Study 1: IKV – Cycling kilometres reimbursement scheme (France)

Within its action plan dedicated to active travel, France has introduced the programme “Indemnité kilométrique vélo” (IKV), a voluntary kilometre-based reimbursement scheme for employees cycling to work (pedelecs and e-bikes are also included in the scheme). The amount of the allowance is fixed at €0.25 per kilometre cycled and up to €200 annually, exempted from social security contributions and income tax. The programme is promoted by the Club des villes et territoires cyclable, a French network of bike-friendly cities, and was first trialled with private companies and then extended to the public sector as well. A national observatory – L’Observatoire de l’indemnité kilométrique vélo – was established to collect data, support the implementation of and follow-up activities relating to the scheme, and share good practices with companies involved.

Learn more: www.villes-cyclables.org/?mode=observatoire-indemnite-kilometrique-velo; www.eltis.org/discover/case-studies/cycling-kilometric-allowance-france

Impact:

| Mobility system efficiency The results of a 2018 survey showed a 69% increase in the number of employees using bicycles among the companies involved, showing a promising upward trend, leading to a reduction in road congestion and an increase in the efficiency of the mobility system. |

| Livable streets Most employers and employees had a positive perception of the initiative, which fostered sociability and well-being within the company. Around the companies involved, the streets tend to become more livable. |

| Protection of the environment Data collected during the initial six-month monitoring period by ADEME, the French Environment and Energy Agency, estimated a reduction of 2.7 tonnes in CO2 emissions, representing an average of 0.03 tonnes per new cyclist per year. |

| Inclusion, equity and accessibility By raising the status and removing the stigma of commuting by bike, IKV increases transportation options for everyone, including people from disadvantaged backgrounds or those unable to buy cars, promoting greater social equity. |

| Safety and comfort As a result many companies have also introduced mobility plans, promoting safety and comfort. |

| Economic value Increasing the number of employees cycling to work allows companies to reduce parking costs (around € 1000 - 1500 per year), while productivity increases, punctuality improves and absenteeism decreases. On the other hand, employees increase their purchasing power (by reducing car expenses), which contributes to reinvigorate local economies. |

| Awareness and acceptability The IKV assessment clearly demonstrates a positive impact on mobility behaviours, while the programme is part of a broader strategy for bicycle promotion. |

Case Study 2: “Job-Rad” – Bicycle as company car (Austria)

The programme “Bicycle as company car” is a scheme through which Austrian companies can provide employees with a company bicycle which can also be made available for every-day private use. Unlike the company car, in Austria the provision of a company bike that can be used for work and private purposes is not a taxable benefit for the employee, while the company can apply for attractive subsidies for buying bikes and/or deduct the costs from its taxable profits. Employees choose the bicycles they want and, in a sort of leasing agreement, pay a monthly usage fee for using the bike.

Learn more: https://radkompetenz.at/en/2336/company-bicycle-instead-of-company-car/; www.klimaaktiv.at/mobilitaet/radfahren/job-rad.html (in German).

Impact:

| Mobility system efficiency Through the scheme, employees commit to use the company bike as often as possible for commuting and business trips, which promotes overall efficiency of the mobility system. |

| Livable streets Increasing bicycle travel makes cities more pleasing, with a more human scale, promoting livable streets. |

| Protection of the environment Through the programme, employers are helping their employees to shift to healthy and environmentally friendly modes of transport, both for work and personal commuting, improving the local environment. |

| Inclusion, equity and accessibility By raising the status and removing the stigma of commuting by bike, IKV increases transportation options for everyone, including people from disadvantaged backgrounds or those unable to buy cars, promoting greater social equity. |

| Safety and comfort Bikes must comply with the Austrian "StVO" road code, including mudguards and lighting, which promotes safety. |

| Economic value No specific data on this topic, but the programme is expected to boost local economies. |

| Awareness and acceptability Integrated with the programme, different information and tips are disseminated, promoting greater awareness in general. |

Legend:

| Very positive | Positive | Neutral | Negative | Very negative |

BusinessWeek Research Services (2008). The Impact of Commuting On Employees: How Commuter Benefits Can Help. Accessed 3 July 2019. Available at: http://www.transitchek.com/uploadedFiles/Transit_Resources/IndustryInformation/2008_Business_Week_Survey.pdf.pdf

Club des villes et territoires cyclables (2018). L’indemnité kilométrique vélo deux ans après sa mise en oeuvre. Paris: Club des villes et territoires cyclables. Accessed 3 July 2019. Available at: http://www.villes-cyclables.org/modules/kameleon/upload/new_ikv_2018_8_pages_web.pdf

ICF (1997). Opportunities to Improve Air Quality Through Transportation Pricing Programs. Accessed 3 July 2019. Available at: https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2016-05/documents/pricing.pdf

Haubold, H. (2016). Commuting: who pays the bill? Overview of fiscal regimes for commuting in Europe and recommendations for establishing a level playing-field. Brussels: European Cyclists’ Federation. Accessed 3 July 2019. Available at: http://www.bike2work-project.eu/en/upload/Ressources_Downloads/141117%20Commuting-%20%20Who%20Pays%20The%20Bill_2.pdf

Savan, B., Cohlmeyer, E., & Ledsham, T. (2017). Integrated strategies to accelerate the adoption of cycling for transportation. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 46, 236–249. Accessed 3 July 2019. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2017.03.002

Shoup, D. (2005). Parking Cash Out. Chicago: Planning Advisory Service. Accessed 3 July 2019. Available at: http://shoup.bol.ucla.edu/Parking%20Cash%20Out%20Report.pdf

Synek, S. & Koenigstorfer, J. (2018). Exploring adoption determinants of tax-subsidized company-leasing bicycles from the perspective of German employers and employees. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 117: 238-260. Accessed 3 July 2019. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2018.08.011

Taylor, I. & Hiblin, B. (2017). Typical Costs of Cycling Interventions: Interim analysis of Cycle City Ambition schemes. Accessed 2 July 2019. Available at: http://www.transportforqualityoflife.com/policyresearch/cyclingandwalking/

VTPI. Victoria Transport Policy Institute (2018). Commuter Financial Incentives. Online Transportation Demand Management (TDM) Encyclopedia. Accessed 2 July 2019. Available at: http://www.vtpi.org/tdm/tdm8.htm