1. Presentation

Each car trip starts and ends in a parking space. Each parking space occupies an area between 15 a 30m2. The vehicle and the driver use between 2 and 5 parking spaces every day. In other words, vehicular parking utilizes too much space and contributes to urban sprawl, expanding trip distance.

In the latest decades, there has been a gradual shift in parking policies, mainly in urban centres, with the implementation of more restrictive measures that seek to balance the different (often competing) space occupancy needs. One of the main strategies implemented in parking management is the pricing of parking spaces and periods.

2. Objectives

- Generating income;

- Reducing traffic issues in specific areas;

- Reducing traffic in a specific area;

- Reducing traffic caused by drivers searching for a parking space;

- Discouraging the use of individual car.

3. Measure´s importance

Managing traffic spaces means managing the index of automobile use and traffic congesting. With the introduction of paid parking, the raising of parking fees or the reduction or limitation of parking availability (See Car parking restrictions), drivers will be pushed to use more sustainable means of transportation. Simultaneously, the income generated by parking pricing can be used to promote alternatives, pulling users towards public transportation, walking, cycling or other sustainable means of transportation.

1. Best Practices

– Parking pricing is one of the measures with the greatest potential in car demand management, due to its minor political and social acceptability barriers. Despite not being a desirable measure, it faces the least resistance among push It is important to mention that the need for pricing depends on the local circumstances. It is always preferable to consider pricing before eliminating or moving parking spaces (See Car parking restrictions).

– The introduction of parking pricing is justified in circumstances where there is a significant parking pressure and high occupancy rates. In such case, one may choose different pricing methods, such as by zone, time periods or, in a more advanced stage, by demand.

– The prices should be well disseminated and predictable. Signs, maps, brochures, sites and other resources should be used to inform users.

– The prices should be established to maintain an 85-90% occupancy rate. The higher the demand for places, the higher the prices, while pricing periods should be shorter and price can increase over time to encourage turnover. Prices should be higher during peak times and lower during off-peak periods. Places with less demand can have smaller prices and discounts, to attract visitors.

– Unlimited use discounts (monthly, bi-annual and annual passes) should be eliminated, to convey the idea of saving more money by reducing car trips. Similarly, parking cost should be greater than public transportation cost.

– Parking management programmes should anticipate the possibility that pricing may result in the relocation of parking to tax free areas, creating more congestion problems in other regions. In response, appropriate regulations and enforcement should be created, in order to maintain the balance between the efficiency of the different transportation modes.

– Parking enforcement should be predictable and educational.

– Parking pricing should be implemented as part of a comprehensive parking management programme, that includes information for the users, commuter trip reduction programme and improvements in alternative transportation modes. Scaling parking supply should not assume that accessibility by private car is a necessity.

– Parking prices should be coordinated in the entire district, or region, to facilitate price comparison between similar areas.

– Use the income from street parking pricing in improvements for local businesses and residents in order to promote more acceptability. The income can also subsidize the operation of sustainable transportation modes.

– Reduce or eliminate the minimal parking requisites, to decide the most adequate supply of parking for each destination.

2. Actions

| Single fee The most simple approach towards pricing aiming towards discouraging car use and fostering sustainable mobility is introducing a single fee in all areas of the city. |

| Zone pricing In medium to big cities, parking pricing can be differentiated between city areas to discourage car parking in central or high density areas. This strategy comes from the understanding of public space as a scarce asset to be actively managed. |

| Zone and time pricing Alongside zone pricing, a parking strategy can differ prices according to the time of the day and duration, with higher rates during peak times and growing rates for larger parking periods, so that medium to long parking periods are discouraged and turnover is promoted. |

| Pricing according to demand Some cities, especially in the North American context, adopt a dynamic pricing strategy, that varies according to the real-time demand (as in the case of hotel prices or in some cases of passenger transport). The dynamic rise in prices penalizes peak times. It’s important to mention that parking management should be implemented from a set of parameters that influence parking demand – land-use, motorization rates and modal split. (See Car parking restrictions). |

1. Impacts

| Mobility system efficiency The rates contribute towards the reduction of car use in favour of other transportation modes, more efficient for the global mobility system. |

| Livable streets Parking pricing reduces automobile use, promoting cycling and walking and humanizing the streets. |

| Protection of the environment It reduces car use and contributes to the reduction of carbon emissions. However, if improperly managed, it can lead to the relocation of parking demand in surrounding areas, creating more environmental problems. |

| Inclusion, equity and accessibility Free parking represents a subsidy for those with more car-ownership who drive more, in prejudice of those with less car-ownership that drive less. This is socially unfair. In that sense, parking pricing, which only falls on those who use it, tends to increase horizontal equity. Simultaneously, pricing represents a greater proportion of income to the less affluent. Overall, by promoting alternative means of transportation, parking pricing benefits people with less income and promotes social equity. |

| Safety and comfort Reducing parking demand reduces traffic and distractions to the driver. Reducing overall traffic should reduce accidents. Since parked cars are associated with higher risks of pedestrian and cyclists collisions, reducing parking demand can lead to safety improvements. |

| Economic value There’s the perception that parking pricing can harm corporate investment and trade. On the contrary, there’s little evidence of the relation between economic growth and parking expenditures. |

| Awareness and acceptability By raising car use costs, other means of transportation will become more attractive, including bicycles, which will tend to be considered more as a means of transportation. |

Legend:

| Very positive | Positive | Neutral | Negative | Very negative |

2. Barriers

| Legal Public authorities have legal control over the fees of the parking places administered by them, but they tend to have no control over private parking spaces. There can be some legal means of regulating private parking. |

| Finance Implementation fees are covered by the income generated. |

| Governance Demands the collaboration of local authorities and private and public parking agencies. |

| Political acceptability Authorities may hesitate in adopting this measure for fear of poor public adherence. |

| Public acceptability Usually, people will complain before the implementation of new parking management measures, but they may become more tolerant once they understand the impacts. |

| Technical feasibility No technical barriers. |

Legend:

| No barrier | Minimum barrier | Moderate barrier | Significant barrier |

3. Budget

| Area | Measure | Unit | Cost | Implementation year |

| Ribeira Brava, Madeira’s Autonomous Region (Portugal) | Acquisition of technical assistance and collective parking meter maintenance of the Parkeon – Stelio or an equivalent brand and management and control of W.P.S brand parking, including preventive and corrective maintenance | 2 years | 20 000,00 € | 2018 |

| Peso da Régua, Vila Real (Portugal) | Concession of land exploration to install and explore parking meters | 10 years | 50,02€ % of liquid income | 2018 |

| Braga, Braga (Portugal) | Acquisition of batteries and printing rolls for parking meters | 8 443,50 € | 2018 | |

| Aveiro, Aveiro (Portugal) | Acquisition of parking meter’s thermal paper | Material for 10 months | 8 485,00 € | 2019 |

| Oeiras, Lisbon’s Metropolitan Area (Portugal) | Road signs installation | Substitution of directional signage from the parking in the Carnaxide Civic Centre and removal of the adherent screen with the inscription “Taxa Social” from parking meters | 1 175,75 € | 2018 |

| Acquisition of preventive and corrective maintenance services | 141 parking meters of the Cale brand for a year | 53 532,00 € | 2019 | |

| Lisbon, Lisbon’s Metropolitan Area (Portugal) | Acquisition of collector cars and coffers for Cale parking meters | 2 years | 19 496,52 € | 2017 |

| Acquisition of services for the development and production of plastic coffers for parking meters, DG model, and the respective acquisition | 24 440,00 € | 2017 | ||

| Almada, Lisbon’s Metropolitan Area (Portugal) | Supply, assemblage and maintenance of parking meters | 15 reconditioned parking meters, coin payments, respective informative signs, pole, the necessary street construction works and 2 year maintenance | 26 137,50€ (32149,12 with IVA) | 2018 |

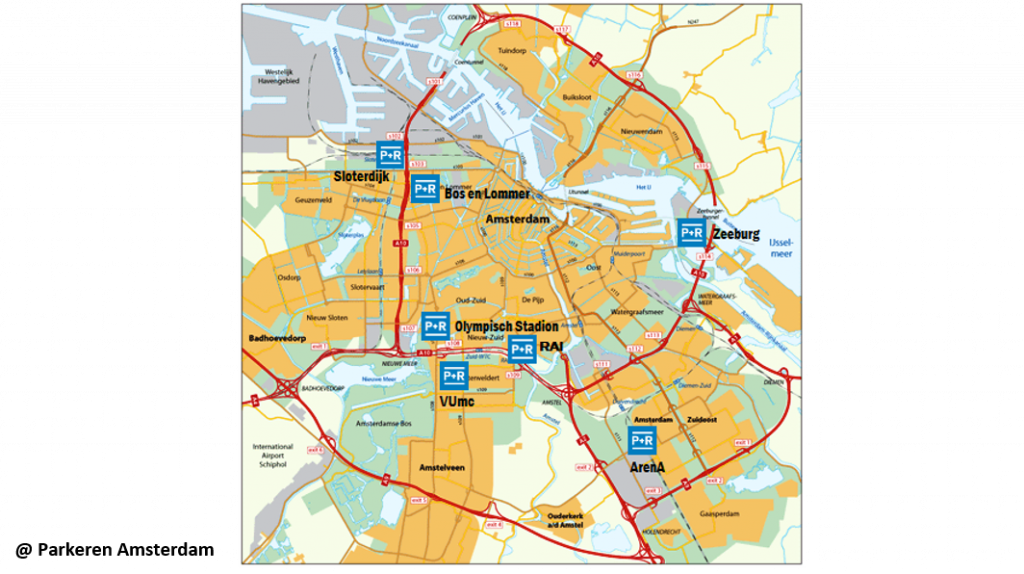

Case Study 1: Parking Pricing in Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Approximately 40% of air pollution in Amsterdam is caused by 10% of cars. Parking fees were introduced to counter decades of car-centric policies and expanded most recently to tackle air quality issues triggered by EU directives regarding NO2 and PM10 emissions. The Dutch government chose to follow the most rigid of the EU interpretations. Paid parking can be found nearly everywhere in the pre-1940s parts of the city and is rapidly spreading to newer areas.

Impact:

| Mobility system efficiency Parking pricing has led to a 20% reduction of traffic in the city’s centre, as well as a 20% reduction in traffic caused by drivers looking for a place to park. |

| Livable streets No data. |

| Protection of the environment The reduction in traffic has an automatic relation with air pollution reduction and the quantity of air pollutants has been steadily decreasing in most part. However, there are several clean air policies currently in use and it’s difficult to unbundle the impacts of one from the others. The hypothesis of reducing pricing fees for electric and ecologic vehicles is being discussed and experimented with. However, despite improving air quality, these vehicles don’t improve energy efficiency or safety and they always demand parking space. |

| Inclusion, equity and accessibility People with physical disabilities and delivery vehicles receive special parking permits. Doctors have designated spaces with the appropriate street signs. Midwifes also have the right to free parking. A different rule applies according to each case. |

| Safety and comfort Amsterdam has several streets where parking guidance was implemented to create safer environments for cyclists and pedestrians. |

| Economic value Parking revenues revert to infrastructure projects. These should be applied in the city-wide mobility strategy, not just the neighbourhood where the revenue is collected. There’s a fund for parking income, but the money can be used in different ways, even to finance child-care centres. |

| Awareness and acceptability No data. |

Case Study 2: Parking Pricing to fund the public bike sharing system in Barcelona (Spain)

Barcelona is notable for being the first city to use 100% of the surplus from on-street parking fees to finance a public bicycle-sharing programme, called Bicing. Faced with congestion from 1.15 million vehicles entering the city centre and 93% of these vehicles looking for parking spaces, in 2005 the city launched the integrated parking regulation programme known as Area Verde, or “Green Zone.” The purpose was to regulate visitor parking supply—limiting parking time using a pricing mechanism to control on-street demand for spaces, while giving priority to residents. The parking project also included converting car spaces to motorcycle parking and Biking stations.

Impact:

| Mobility system efficiency Congestion has gone down between 5 and 10%. In 2007, the modal transference was, approximately, of one third for each transport, between public transport, private motorized vehicle and non-motorized transport. Approximately, 4% of Bicing drivers are previous automobile drivers and almost 5% are old passengers or motorcyclists. |

| Livable streets Barcelona has also been removing parking to improve public space for pedestrians. The historic town centre is almost fully pedestrian and there are many of streets where only taxis, residents’ cars and delivery vehicles can enter. When AREA Verde was launched, all revenues were directed towards a special fund focused on mobility. The first programme to be financed was the implementation of 30 mph Zones and the remaining funds was redirected towards Bicing, which has 440 stations and almost 300 of them are in the street, each using 3 to 4 converted parking spaces, which equals a recovery of almost 1200 spaces. |

| Protection of the environment The modal transfer translates in in a reduction of private vehicle use with beneficial effects in the environment, namely the reduction of polluting emissions and energy consumption. |

| Inclusion, equity and accessibility No data. |

| Safety and comfort No data. |

| Economic value The call for Bicing was launched in 2006, a year when the city had a surplus of 12 million €. |

| Awareness and acceptability No data. |

Case Study 3: Workplace Parking Levy (WPL) in Nottingham, UK

A Workplace Parking Levy (WPL) is a charge on the provision of workplace parking places to be paid by the employer to the local authority. Nottingham City Council was the first local authority in the UK to have introduced such a levy. It was intended to be part of an overall transport package, in line with local and regional transport policy. The WPL is intended to encourage commuter travel planning and for employers to better manage their car parks. Employers are more likely to introduce or improve staff travel planning schemes, and manage their car parks effectively, which should have a positive impact on reducing traffic growth. Money raised from the Workplace Parking Levy is ring-fenced for local public transport improvements. The WPL provides funding for extensions to the existing tram system, the redevelopment of Nottingham Railway Station, and sustaining and developing the supported Link bus network, as well as parking management support measures.

Learn more: http://www.eltis.org/discover/case-studies/encouraging-nottingham-employers-improve-staff-travel-planning-uk

Impact:

| Mobility system efficiency Together with the tram, train and bus improvements, parking pricing is predicted to reduce traffic from 15% to 8% until 2021. It’s expected a 20% increase in public transportation trips inside and outside of the city. A 45% rise in search for Park and Ride (parking and public transportation integrated ticket) is also expected. The improvements in transportation will remove approximately 2,5 million cars from Nottingham roads. |

| Livable streets Visiting vehicles aren’t taxed, thus avoiding adverse impacts in the number of people and possible clients entering the city. |

| Protection of the environment No data. However, the increase in public transportation use would reduce air and noise pollution. |

| Inclusion, equity and accessibility The programme includes free parking for disabled people and other exceptions. |

| Safety and comfort No data. |

| Economic value In its first year, the fee should generate approximately 8 million £ (11 million €) resulting from the 3000 sites in the city. Visiting vehicles aren’t taxed, thus avoiding adverse impacts in the number of people and possible clients entering the city. |

| Awareness and acceptability No data. |

Legend:

| Very positive | Positive | Neutral | Negative | Very negative |

KonSULT. Knowledgebase on Sustainable Urban Land use and Transport. (2014). Parking Charges. Accessed 3 July 2019. Available at: http://www.konsult.leeds.ac.uk/pg/25/

Kodransky, B. M., & Hermann, G. (2011). Europe’s Parking U-Turn: From Accommodation to Regulation. Accessed 3 July 2019. Available at: https://itdpdotorg.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Europes_Parking_U-Turn_ITDP.pdf

Litman, T. (2018). Parking Pricing Implementation Guidelines: How More Efficient Parking Pricing Can Help Solve Parking and Traffic. Accessed 3 July 2019. Available at: https://www.vtpi.org/parkpricing.pdf

Rye, T., Mingardo, G., Hertel, M., Thiemann-Linden, J., Pressl, R., Posch, K., Carvalho. M. (2015). 16 Boas razões para uma Gestão do estacionamento. Accessed 3 July 2019. Available at: http://www.push-pull-parking.eu/docs/file/20150521_push_pull_a4_pt_web.pdf

VTPI. Victoria Transport Policy Institute (2018). Parking Pricing. Online Transportation Demand Management (TDM) Encyclopedia. Accessed 3 July 2019. Available at: www.vtpi.org/tdm/tdm26.htm