1. Presentation

Network that results from a broad vision integrating the transport system and the built environment. It corresponds to a specific infrastructure that combines different components of the road network and is preferentially or exclusively oriented to bicycle users.

A well-connected cycling network provides a safe, direct and enjoyable mobility experience, enabling people of all ages and abilities to reach their destinations.

2. Objectives

- Providing safe, comfortable, fun and direct cycling routes in strategic zones to increase the cycling accessibility levels to the various services and activities;

- Ensuring the conditions for the bicycle to be seen as a safe and efficient mode of transport, increasing its competitiveness;

- Encouraging cycling among the different social strata;

- Reducing congestion and pollution;

- Creating more inclusive and accessible streets.

3. Measure’s importance

The provision of an integrated cycling network provides comfort, safety and efficiency for bicycle commuting, as well as a more favourable environment for the other active modes of transport. It is a key step towards creating the conditions for everyone (including children, women, the elderly) to feel able to cycle with safety and autonomy, reducing the need to use the car in the territory served by the network. In addition, the measure contributes to reducing the risk of accidents and the feeling of insecurity in the public space, with low construction and maintenance costs when compared to the infrastructure for motor vehicles.

1. Good Practices

– In order to promote cycling as a daily transport mode, the focus should be to set up a utility network, as opposed to a recreational network. The goal of a utility or functional cycling network is to connect destinations, as directly as possible, for functional trip purposes such as shopping, working, education, socio-cultural visits etc. (Dufour, 2010).

– A well-organized cycling network should allow cyclists to easily reach any destination with comfort and safety through an interconnected set of safe and direct routes that cover a particular area or the whole city and should be based on routes, not on lanes or tracks without continuity.

– The guiding principle should be: mixing if possible and segregating if necessary – safety is always the overriding concern (Dufour, 2010):

a) Mixing where this is safe or can be made safe (speeds up to 30 km/h) – local routes should run through quiet, traffic-calmed areas without any special physical provision for cyclists, except occasional markings or signage. In many cases, the impact of motor traffic can be reduced by various ways of traffic reduction and traffic calming. This “invisible infrastructure” can have a greater impact on cycling levels than specific infrastructure, since reducing the volume and speed of motor traffic is the safest option, keeping the streets accessible to cars, but allowing cyclists and pedestrians to move safely and freely. In this way, all the local streets become part of the cycle network.

b) Segregating where safety requires it, because of high traffic volumes and speeds, as a cycling network can not only cover streets with quiet traffic. On roads with speeds between 30 and 50 km/h visual segregation (bike lanes) is sufficient; on roads with high traffic flows (average annual daily traffic above 10,000) and speeds above 50 km/h, physical segregation (bike tracks) must be guaranteed. The provision of quick and direct links between major urban destinations should be the backbone of the cycling network, interconnecting quitter local areas places, which should be accompanied by an adequate approach to intersections and other points of conflict (see Safe and efficient intersections).

– A cycling network should have as quality criteria: safe routes (using strategies that allow to address points of conflict), direct (taking cyclists to their destinations by the shorter and quicker routes), coherent (connected with other networks, namely public transport, and with major trip generation poles), comfortable (with even road surface, good lightning, topographically adjusted, etc.) and fun (taking cyclists through pleasant surroundings covering heritage, functional or scenic points of interest).

– The steps for designing a cycling network should include: determining the main origin-destination areas and connections; defining the preferential routes for the main origin-destination; creating a hierarchy in the network: main routes (connection at the city or region level); top local routes (distribution function in built-up areas) and local routes that have an access function at the neighbourhood level and include all streets or lanes that can be used by cyclists, connecting buildings and other origins and destinations to higher-hierarchy routes;

– The design of cycling infrastructure must take into account the physical space required for cycling: the dimensions of the cyclist and the bicycle, as well as the physical characteristics of the activity of riding a bicycle, favouring unidirectional cycle paths in each direction of the roadway over bidirectional ones.

– The design of the network should be integrated with safe and efficient intersections and with a bicycle parking network .

– Monitor citizens ‘adaptation to changes and reformulate measures to respond to users’ needs, without compromising sustainable ideals (See Management, monitoring and maintenance).

– Explain the principles behind the measures taken so that their need and functioning are clear (See Information).

2. Actions

| CYCLE TRACK | Space with physical segregation from motorised traffic, generally used exclusively by people who cycle, implemented on the side of the roadway or with its own route. It is the highest quality infrastructure for bicycle user as it physically separates them from motorized traffic, providing comfort and safety even for less experienced cyclists. It can be one-way or two-ways. The implementation of segregated solutions in urban areas, especially two-way cycle path, must take into account the approach to intersections. Learn more: ec.europa.eu/energy/intelligent/projects/sites/iee-projects/files/projects/documents/presto_fact_sheet_cycle_tracks_en.pdf |

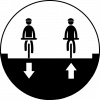

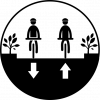

| Two-way cycle track Recommended dimensions: > 2,50 m (minimum: 2,20 m); Additional safety zone, if necessary (e.g. car parking): 0,80 m. Advantages: Safe and exclusive space that raises comfort and reduces the risk of collisions with vehicles. More attractive to a wide range of cyclists at all levels and ages. Disadvantages: Implementation cost. Space consumption. Lack of visibility between drivers and cyclists, since the latter can appear in the contra-flow. In a consolidated urban environment, it can aggravate the performance of intersections. |

| One-way elevated cycle track Recommended dimensions: > 2 m (minimum: 1,30 m); Additional safety zone, if necessary (e.g. car parking): 0,80 m. Advantages: Increases comfort and safety feeling and reduces the risk of collisions with vehicles. Encourages cyclists to use the bike path instead of the sidewalk. Minimizes maintenance costs since there is no wear from motor vehicles. More attractive to a wide range of cyclists at all levels and ages. Disadvantages: Implementation cost. Space consumption. In a consolidated urban environment, it can aggravate the performance of intersections. |

| One-way cycle track Recommended dimensions: > 2 m (minimum: 1,30 m). Advantages: Prevents double parking along the track. Disadvantages: Possibility of conflict with parked vehicles - "dooring" effect. Implementation cost. Space consumption. In a consolidated urban environment, it can aggravate the performance of intersections. |

| Shared use track for Pedestrians and Cyclists Solution to be avoided and to be considered only in exceptional situations (low pedestrian density and width above 4 meters). Advantages: Separation of motorized traffic. Disadvantages: Fosters permanent conflicts against the loss of quality of service for both space users. |

| Cycle trails (“solitary tracks”) Touristic cycle tracks. Applicable mainly for recreational and leisure routes; along railways, using, for example, deactivated railways, between urban agglomerations, etc. Generally, they are bidirectional and may be shared share with non-motorized touristic modes. Minimum width: 2,50 m. Advantages: Increases comfort and safety feeling and reduces the risk of collisions with vehicles. Greater contact with nature; less contact with visual, sound and atmospheric pollution. Offers favourable conditions for leisure activities. Disadvantages: Higher implementation and maintenance cost. Potential conflicts with pedestrians. Not utilitarian. |

| CYCLE LANE | On-road space for people who cycle, with visual segregation through road markings separating them from other road traffic; indicated in moderated-traffic roads and speeds up to 50 km/h. It’s a flexible and quick solution for pre-existing roadways. Learn more: ec.europa.eu/energy/intelligent/projects/sites/iee-projects/files/projects/documents/presto_fact_sheet_cycle_lanes_en.pdf |

| Cycle lane with buffer zone Recommended dimensions: > 2m (minimum: 1,50 m). Buffer zone: 0,80 m. Advantages: Ensures a secure distance between the driver and the cyclist. Increases the feeling of comfort and safety. Reduces the risk of collisions with vehicles. Disadvantages: Requires that space with reasonable dimensions. Special attention should be given to intersections and traffic stops to manage interactions particularly, between bicycles and pedestrians. |

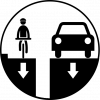

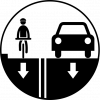

| Conventional one-way cycle lane Recommended dimensions: > 2m (minimum 1,50m). Advantages: Increases the predictability of the positioning and interaction of cyclists and drivers. Disadvantages: Implementation cost. Space consumption. In a consolidated urban environment, it can aggravate the performance of intersections. Possibility of conflict with parked vehicles - "dooring" effect. |

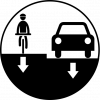

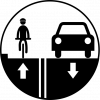

| Contra-flow cycle lane On principle, it is advisable to exempt cyclists from one-way restrictions, allowing them to move in the opposite direction*; however, on roads with higher speeds or with a high traffic volume, the provision of contra-flow cycle lanes may be indicated, which must comply with the recommended dimensions (lane> 1,50 m). Advantages: Increases accessibility and connectivity for cyclists. Reduces distance, travel time and the number of crossings. Encourages cyclists to use the lane instead of the sidewalk. Drivers and cyclists become more alert as they have mutual eye contact. Disadvantages: Implementation cost. Space consumption. In a consolidated urban environment, it can aggravate the performance of intersections. At an early stage, it may generate conflicts at intersections because it is against the normal disposition of drivers and other road users. |

| ADVISORY CYCLE LANE | Coexistence situation where bicycles share the road space with motor vehicles (road space), suggesting the space for cyclists on the road through road markings. They usually are unidirectional but there may be one-way roads where bicycle can travel in both directions (for example, zones 30). Solution applicable mainly within the urban network, in neighbourhoods and central areas. The design of advisory lanes, sharing of road space with motorized traffic, should take into account the principles associated with the concept of traffic calming through urban design. It can be an alternative in narrow streets where space for a cycle lane is lacking, drawing the attention of car drivers to the potential presence of cyclists and their right to be there. |

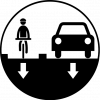

| Sharing with the car If there are road markings, the recommended dimensions are: Width: 0,90 m (minimum 0,70 m); Additional safety zone, if necessary (e.g. car parking): 0,80 m. Advantages: Low cost. No conflict with parked cars. Power to generate network - multiplicative character given its simplicity and potential for generalization. Does not lead to more conflicts (especially with pedestrians). Takes the bike as a vehicle (and not as a segregated/ exclusive mode with its own treatment! - city is mix!). Disadvantages: Only applicable when speed differences are reduced. Requires evaluating the volume and type of traffic. Initially it is more dedicated to urban and experienced cyclists (less leisure). Potential conflict with Public Transport (reduces its speed - note that in a consolidated urban environment this does not happen (stops every 250 meters). Complementary measures such as horizontal and vertical signage, speed management, safe and convenient crossings should be used. security requires strict compliance with traffic rules and traffic calming. At an early stage, it requires information and awareness campaigns. |

| Sharing with the bus Advantages: Efficient for those who are already experienced cyclists. Disadvantages: For the vast majority of potential cyclists, sharing space with large vehicles is unpleasant. Increased feeling of discomfort and insecurity. The stop-start nature of the bus may not be compatible with the cyclist's steady speed and may lead to dangerous changes of direction. |

| MIXED-USE ZONES | Also known as shared zones and meeting zones, they are designed to encourage different modes of transport to co¬exist on the same roads and public spaces. This can include cyclists mixing with pedestrians, motorised vehicles, or both. Learn more: ec.europa.eu/transport/themes/urban/cycling/guidance-cycling-projects-eu/cycling-measure/mixed-use-zones_en |

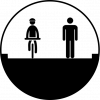

| Cyclists' access to pedestrian zones Usually only requires additional signage to exempt cyclists from restriction to vehicles. At higher densities, some kind of visual or level separation should be used. Advantages: Improves cycling network quality: better (direct) shortcuts, away from motorized traffic (security), easier access to destinations (cohesion), pleasant environment (attractiveness). Implementation is mostly just a matter of signalling and marking. Disadvantages: Implementing bicycle access to busy areas requires a physical separation integrated into the street design. |

| Shared streets Many narrow streets function informally as shared streets. By removing the formal distinctions between spaces dedicated to pedestrians, cyclists and motor vehicles, the street is shared by all, influencing a more conscious behaviour by each user. Formal shared streets should be designed with a focus on pedestrians and cyclists and use systematic traffic calming measures Shared streets remove the traditional segregation between modes of transport and is a quick and inexpensive way to introduce conditions for cycling; they should be implemented in places where pedestrian activity is high and traffic volumes are low or discouraged. |

* On one-way streets, it is advisable to adopt regulations that allow contra-flow cycling. This is a simple regulatory measure, implemented through proper signalling, and it is an effective way to increase connectivity and convenience of cycling routes, as unidirectional roads can create significant detours for cyclists, while contraflow cycling creates faster shortcuts. Learn more: Presto Contra-flow cycling.

For more information and detailed guidance on cycling infrastructure design, see: ec.europa.eu/transport/themes/urban/cycling/guidance-cycling-projects-eu/cycling-infrastructure-quality-design-principles/existing-guidance-and-standards_en

1. Impacts

| Mobility system efficiency The provision of a cycling network encourage an increase in the cycling modal share, contributing to reducing congestion and increasing the efficiency of the mobility system. |

| Livable streets The provision of cycling routes and areas encourages the organization of the public space and promotes increased humanization and reduction of functional conflicts. |

| Protection of the environment Studies indicate that the provision of a cycling network favours modal shift to cycling, which resulting in the mitigation of air pollution and noise levels, including reduced CO2 emissions. |

| Inclusion, equity and accessibility Lower income groups may benefit from the improved and lower-cost mobility options and that cycling represents. |

| Safety and comfort The provision of a cycling network improves the users’ feeling of safety and comfort towards this mode. |

| Economic value Providing quality cycling routes and areas in a local centre encourages an increased use of stores and services in the local area. |

| Awareness and acceptability Evidence shows that the presence of cyclists in the city stimulates and promotes change in commuting habits. Consequently, the provision of cycling networks may influence more sceptical groups to use the bicycle more frequently. |

Legend:

| Very positive | Positive | Neutral | Negative | Very negative |

2. Barriers

| Legal In most cases, there are no obvious legal barriers to implementing cycling networks. |

| Finance Planning and implementing a cycling network can be an expensive undertaking, although there is a substantial cost difference between cycle tracks, cycle lanes and coexistence. The need to prioritise scarce public funds for a minority of users (in the case of starter cities) is a significant barrier. |

| Governance The implementation process may involve public authorities and potentially corporations, cycling charities and other interest groups. |

| Political acceptability In starter cycling cities, as cyclists represent a minority, measures focused on bicycle often have less priority within the policymaking process than those measures related to motorised vehicles. |

| Public acceptability Support from various groups as well as pro-cyclist lobbies is expected. However, it is also expected the reaction from those who are contrary to investments in cycling, especially if it undermines the investment in other modes of transport or public services. |

| Technical feasibility The implementation of cycling infrastructure requires careful planning and design. Nevertheless, in comparison to other transport modes, technical requirements are not complex. |

Legend:

| No barrier | Minimum barrier | Moderate barrier | Significant barrier |

3. Budget

| Area | Measure | Unit | Cost | Implementation year |

| Lisbon, Lisbon Metropolitan Area (Portugal) | Installation of bicycle stair ramps | 32 bicycle stair ramps | 150 000,00 € | 2015 – 2016 |

| Cantanhede, Coimbra (Portugal) | Construction of bike track | Bike track along national road EN109 (Tocha) | 40 855,50 € | 2019 |

| Trofa, Porto Metropolitan Area (Portugal) | Technical advisory services and developing plans | Trofa city and interurban connections to Santo Tirso and Vila Nova de Famalicão | 33 500,00 € | 2016 |

| Maia, Porto Metropolitan Area (Portugal) | Construction of bike track | 2,8 km | 231 379,08 € | 2014 |

| Viana do Castelo, Viana do Castelo (Portugal) | Construction of bike track | Riverfront | 493 009,37 € | 2018 |

| Polytechnic Institute of Leiria, Leiria (Portugal) | Create and improve ramps, pavements and signs that facilitate pedestrian and bicycle traffic | University campus | 23 547,12 € | 2018 |

| Seville, Andalusia (Spain) | Construction of bike tracks | 180 km | 662 000,00 € | 2007 |

| Great Manchester (U.K.) | Replacement of bus stops and placement of new shelters | 90% of 3 bus stops/km | 1,45 million £ | Data from a 2017 study |

| Updating intersections | 5 intersections | |||

| Creation of new intersections | 0.5 intersections /km | |||

| Rehabilitation of existing signs | ||||

| Rehabilitation of motorway | Specific points | |||

| Yorkshire (U.K.)

|

Replacement and creation of bus stops’ shelters | Over 4 bus stops/km | 1,15 million £ | Data from a 2017 study |

| Creation of new intersections | 1 | |||

| Updating intersections | 4 | |||

| Integration of shared transit section | 1 section | |||

| Cambridge, Cambridgeshire (U.K.) | Replacement and creation of bus stops | 3 bus stops/km | 0,96 million £ | Data from a 2017 study |

| Floor elevation | Specific points | |||

| Preventive rehabilitation of road and sidewalk | Specific points | |||

| Salford, Great Manchester (U.K.)

|

Construction of bike lanes on the 2 sides of the roadway limited by plastic pillars and intermittent lights, plus road resurfacing | 2,2 km | 0,24 million £ | Data from a 2017 study |

| Norfolk (U.K) | Construction of new on-road cycle lanes and tracks | 2.8 km | 0,46 million £ | Data from a 2017 study |

| Rehabilitation of pre-existing cycle tracks and grade-separated facilities | 0,42 km | |||

| Advanced stop areas at signals | 4 | |||

| Cycle zebras | 2 | |||

| Other new crossings | 5 | |||

| Speed humps | ||||

| Traffic management alterations | ||||

| Parking alterations | ||||

| Public realm improvements | ||||

| Tree planting | ||||

| New overhead path lighting, motion-activated through sensitive areas | 1,4 km | |||

| Signage | 184 000,00 £ (included in the 0,46 million £ total) | |||

| Birmingham (U.K) | Information totems | 2 km | 43 000,00 £ (included in the 0,19 million £ total) | Data from a 2017 study |

| Ramped access to cycle track | 1 access | 250 000,00 £ (not included in the 0,19 million £ total) | ||

| Ramped access to cycle track | 1 access | 450 000,00 £ (not included in the 0,19 million £ total) | ||

| Bristol (U.K.) | Refurbishment of a pre-existing | widening by 0.4m to 2.3m | 0,50 million £ | Data from a 2017 study |

| Nonslip surfacing laid to the bridge | ||||

| Installation of ramps compliant with disability legislation | 2 ramps | |||

| Lighting installation | ||||

| Austria | Construction of 3m-wide, asphalt bike track | 1 m | 423,00 € | Data from a 2013 study |

| 370,10 € | ||||

| Fast track add-on | 7,00 € | |||

| Construction of lanes in roadways | 599,20 € | |||

| Bike lane marking | 10 km | 50 000,00 € | ||

| Signalling cycling network with orientation system | 35 km | 50 000,00 € | ||

| Building and defining bike routes | Up to 10 routes | 50 000,00 € |

Case Study 1: Cycling network in Seville (Spain)

The Seville City Council recognized the excessive use of motor vehicles and the environmental consequences. As a solution to such problem, the city has developed specific strategies to promote the use of bicycles as an effective mode of transportation, by providing a wide network of bicycle routes throughout the city, which ensure important connections between major points in the city. The following specific instruments helped the implementation of this cycleway network: the creation of the Bicycle Master Plan and the Pedestrian and Cyclist Traffic Law.

Learn more: www.sevilla.org/sevillaenbici/

Impact:

| Mobility system efficiency The experience of Seville shows that the fast implementation of segregated cycling network can make bicycle usage safe, easy and comfortable, increasing bicycle modal share substantially even in cities without prior tradition. In Seville the number of cyclists grew around 6 times over a period of five years. |

| Livable streets The provision of cycling network has contributed to a modal shift towards the bicycle, which has provided opportunities for social interaction, as well as more active and dynamic streets. |

| Protection of the environment Seville experienced a rapid growth in urban cycling, starting with a bicycle modal share of 0.6% in 1991 to 9% in the end of 2011. Studies identified a bicycle usage increase of 5.6% after the cycling network implementation. The reduction in greenhouse emissions are over 8,000 tons of CO2. |

| Inclusion, equity and accessibility The cycling network is an inclusive infrastructure, where the various groups can benefit from using the bicycle as a cheap and convenient commuting mode. A public opinion poll, in Seville, showed a growing population’s support, since people consider the cycling infrastructure necessary for the safe circulation of cyclists. However, some controversy has arisen regarding the elimination of about 8000 parking spaces. |

| Safety and comfort In Seville, the implementation of the cycling network and the consequent increase of the cycling level was associated with the increase in the number of traffic accidents involving cyclists in the first years. However, such increase was not linear, with a significant fall between the years of 2006 and 2011. It should be noted that the indicator used, number of accidents, is not the most suitable (the indicator to be used should be the number of accidents per kilometres travelled by bicycle). |

| Economic value Providing quality bicycle routes at urban centres may encourage greater use of local stores and services, although this case study does not provide evidence. |

| Awareness and acceptability The provision of cycling infrastructure and complementary measures have generated increased public awareness of the positive impacts of cycling. In Seville complementary measures were implemented in the university sector and within the public transport system (bus + bicycle integration). The main idea behind the model was to make cycling safe, convenient and comfortable for everyone. |

Case Study 2: Cycling Network in München (Germany)

Since 1986, the city of Munich has been developing its network of cycle paths through a series of Transport Development Plans for Bicycles. The network covers around 1200 km and embody the following typologies: 14 signed routes spreading out from the city centre, together with three ring routes that provide good connectivity and mobility; 17 bicycle roads that are reserved entirely for cyclists; the introduction of contraflow lanes for cyclists on one-way streets for motorized traffic.

Impact:

| Mobility system efficiency Since the introduction of the cycling network in Munich, there was a significant increase of 14% in the bicycle modal share, between 2000 and 2008. |

| Livable streets The number of journeys by bicycle increased, while the proportion of journeys on foot decreased. Walking and cycling have similar benefits regarding social interaction and promotion of livable streets. |

| Protection of the environment There is no detailed data proving the mitigation of CO2 and other pollutants within such project. However, relatively high bicycle modal share, combined with walking, contributes to reducing noise and atmospheric pollution. |

| Inclusion, equity and accessibility The cycling network is an inclusive infrastructure where diverse groups can benefit from cycling as a cheap and convenient way to travel. Improvements in infrastructure can make cycling more attractive to a number of social groups, including seniors, women and children. |

| Safety and comfort The perception of safety and comfort has contributed to the increased bicycle modal share. |

| Economic value Providing quality cycling network in an urban centre encourages greater use of local stores and services, although the study case does not provide evidence to support this. Munich invested a considerable amount of funds in its cycling plan. In 2012, the annual allowance for bicycle transport was around €4.5 million. |

| Awareness and acceptability The provision of cycling infrastructure and complementary measures have generated greater public awareness on the positive impacts of cycling, although this case study does not present evidence of this effect. |

Legend:

| Very positive | Positive | Neutral | Negative | Very negative |

Bmvit (2013) Radverkehr in Zahlen. Accessed 2 July 2019. Available at: www.bmvit.gv.at/service/publikationen/verkehr/fuss_radverkehr/downloads/riz201503.pdf

Bmvit (2017) Kosteneffiziente Maßnahmen zur Förderung des Radverkehrs in Gemeinden. Viena: Radetzkystraße

Bus Lanes Provide Good Conditions for Cycling. Cycling Fallacies. Accessed 12 December 2018. Available at: cyclingfallacies.com/en/31/bus-lanes-provide-good-conditions-for-cycling

CML. Câmara Municicpal de Lisboa (2015). Lisboa amiga das Bicicletas. Accessed 2 July 2019. Available at: www.cm-lisboa.pt/noticias/detalhe/article/lisboa-amiga-das-bicicletas

CROW (2016). Design Manual for Bicycle Traffic. Ede: Crow.

Dufour, D. (2010). Cycling Infrastructure. PRESTO Cycling Policy Guide. Accessed 27 March 2019. Available at: ec.europa.eu/energy/intelligent/projects/sites/iee-projects/files/projects/documents/presto_policy_guide_cycling_infrastructure_en.pdf

ETSC. European Transport Safety Council. (2018). Briefing Contraflow Cycling. Accessed 12 December 2018. Available at: etsc.eu/wp-content/uploads/Briefing-Contraflow-Cycling.pdf

European Commission (2019). Existing cycle infrastructure quality design guidance (and standards). Accessed 20 July 2019. Available at: ec.europa.eu/transport/themes/urban/cycling/guidance-cycling-projects-eu/cycling-infrastructure-quality-design-principles/existing-guidance-and-standards_en

Heydon, R., & Lucas-Smith, M. (2014). Making space for cycling: A guide for new developments and street renewals. Cyclenation. Accessed 22 July 2019. Available at: http://www.makingspaceforcycling.org/MakingSpaceForCycling.pdf

IMPIC. Base: Contratos públicos online. Accessed 2 July 2019. Disponível em: www.base.gov.pt/Base/pt

IMTT (2011). Princípios de Planeamento e Desenho. Colecção de Brochuras Técnicas / Temáticas: Rede Ciclável – princípios de planeamento e desenho. Accessed 2 July 2019. Available at: www.imt-ip.pt/sites/IMTT/Portugues/Planeamento/DocumentosdeReferencia/PacotedaMobilidade/Documents/Pacote%20da%20Mobilidade/Rede%20Cicl%C3%A1vel_Princ%C3%ADpios%20de%20Planeamento%20e%20Desenho_Mar%C3%A7o%202011.pdf

Marqués, et al. (2015). How infrastructure can promote cycling in cities: Lessons from Seville. Research in Transportation Economics, 53, pp 31-44. Accessed 12 February 2019. Available at: www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S073988591500061X

NACTO. National Association of City Transportation Official. (2013). Bicycle Boulevards. Urban Bikeway Design Guides. Accessed 12 December 2018. Available at: https://nacto.org/publication/urban-bikeway-design-guide/bicycle-boulevards/

NACTO. National Association of City Transportation Official. (2013). Buffered Bike Lanes. Urban Bikeway Design Guides. Accessed 12 December 2018. Available at: https://nacto.org/publication/urban-bikeway-design-guide/bike-lanes/buffered-bike-lanes/

NACTO. National Association of City Transportation Official. (2013). Conventional Bike Lanes. Urban Bikeway Design Guides. Accessed 12 December 2018. Available at: https://nacto.org/publication/urban-bikeway-design-guide/bike-lanes/conventional-bike-lanes/

NACTO. National Association of City Transportation Official. (2013). One-Way Protected Cycle Tracks. Urban Bikeway Design Guides. Accessed 12 December 2018. Available at: https://nacto.org/publication/urban-bikeway-design-guide/cycle-tracks/one-way-protected-cycle-tracks/

NACTO. National Association of City Transportation Official. (2013). Shared Streets. Urban Bikeway Design Guides. Accessed 12 December 2018. Available at: https://globaldesigningcities.org/publication/global-street-design-guide/streets/shared-streets/

NACTO. National Association of City Transportation Official. (2013). Two-Way Cycle Tracks. Urban Bikeway Design Guides. Accessed 12 December 2018. Available at: https://nacto.org/publication/urban-bikeway-design-guide/cycle-tracks/two-way-cycle-tracks/

PRESTO. Promoting Cycling for Everyone as a Daily Transport Mode (2010). Cyclists and pedestrians. 25 PRESTO Implementation Fact Sheets. Accessed 1 July 2019. Available at: http://www.rupprecht-consult.eu/uploads/tx_rupprecht/07_PRESTO_Infrastructure_Fact_Sheet_on_Cyclists_and_Pedestrians.pdf

PRESTO. Promoting Cycling for Everyone as a Daily Transport Mode (2010). Presto Cycling Policy Guide: Cycling Infraestructure. Accessed 10 July 2019. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/energy/intelligent/projects/sites/iee-projects/files/projects/documents/presto_policy_guide_cycling_infrastructure_en.pdf

PRESTO. Promoting Cycling for Everyone as a Daily Transport Mode (2010). Contra-flow Cycling. 25 PRESTO Implementation Fact Sheets. Accessed 15 July 2019. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/energy/intelligent/projects/sites/iee-projects/files/projects/documents/presto_fact_sheet_contra_flow_cycling_en.pdf

Taylor, I. & Hiblin, B. (2017). Typical Costs of Cycling Interventions: Interim analysis of Cycle City Ambition schemes. Accessed 2 July 2019. Available at: http://www.transportforqualityoflife.com/policyresearch/cyclingandwalking/

USE. Urban Sustainability Exchange. Cycle-lane network Seville. Accessed 14 December 2018. Available at: https://policytransfer.metropolis.org/case-studies/cycle-lane-network-seville